Exploring the Historical Maps of Colonial New England

How to Analyze an Historical Map

First:

Look over the map and examine its parts.

-

What is the title of the map?

-

Who made it? When is it from?

-

What kind of map is it? (political, exploratory, topographical, military, etc.)

-

What key components do you see? Is there a legend, scale, compass, cartes-à-figures, etc.

-

What materials were used to create the map? (pencil, ink, paints, paper, wood, tools, animal hide, printing press, etc.)

-

What places are labeled or shown? What isn't shown?

Next:

Analyze and make sense of it.

-

What was happening in history when this map was created?

-

Knowing that, why do you believe this map was drawn?

-

How could this map help you in your research?

-

What supporting documents or evidence do you need to help you understand more about the map?

Lastly:

What have you learned from examining this map that you might not learn from other sources?

Generalized Spatial Analysis of Early New England Maps

Early Maps

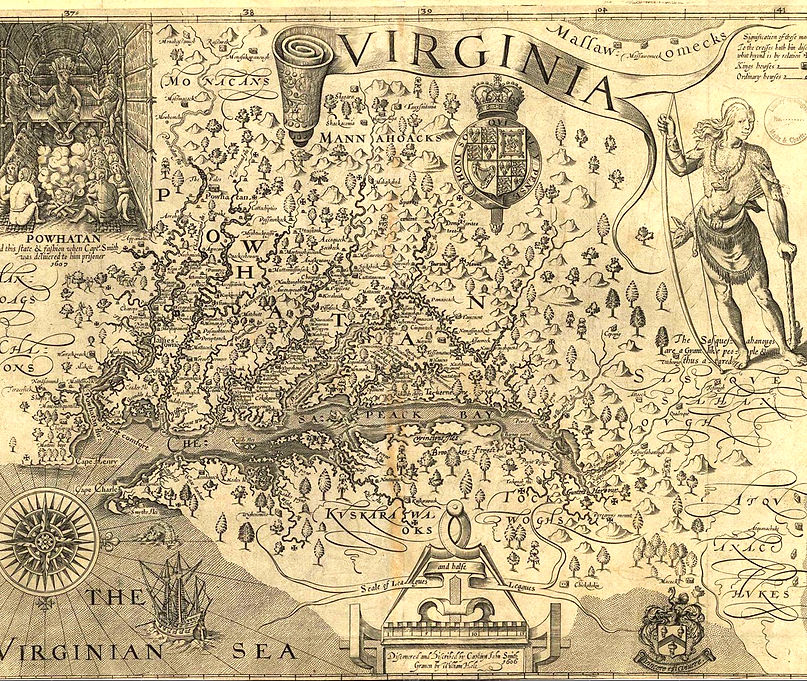

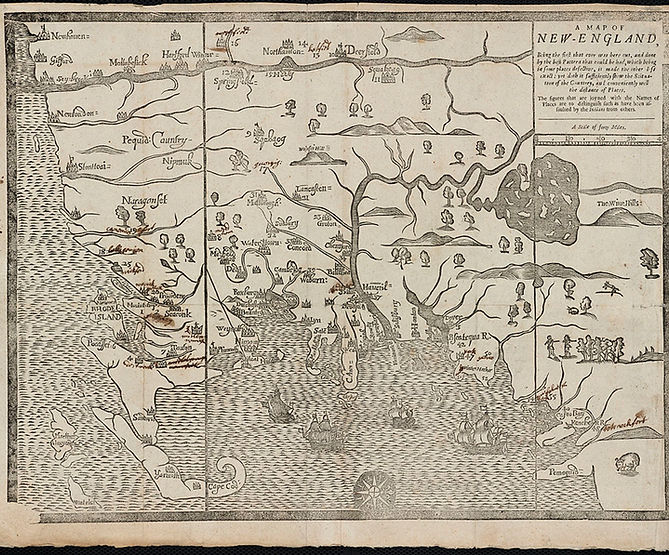

Early cartographers such as John Dee, John Smith, and even Samuel de Champlain charted maps largely based on the idea of a continent in need of settlers. It was easy to justify colonization of an empty land, a sort of vacuum domicilium, unused land that was ready to be settled. Indigenous people, if they were portrayed in maps, were often represented as wilderness features, as in the Forster Map where a single tree indicated an Indigenous village with no other label.[1] Or they served as ornamentation and embellishment, as in Samuel de Champlain’s 1612 Carte Geographique de la Nouvelle France.[2]

Cartographers certainly recognized Indigenous habitation of New England, but actively diminished the Indigenous presence in the landscape. Historian Brian Harley noted that cartographers, through the deliberate use of silences, helped create the idea of the “American wilderness,”an unsettled land largely devoid of people.[3] This concept disenfranchised the Indigenous population by not recognizing or dismissing the fact that they lived in sovereign man-made built complex communities and instead regulated them as part of a natural environment. These imperialistic views were intentional, power-based, and political, that is, not based on ignorance or a lack of information. It was a deliberate and imperialistic choice to minimize or exclude the Indigenous sovereign presence from the cartographic landscape to justify imperialistic claims in North America.

[1]. Forster and Hubbard, A Map of New England, (1675), Appendix, Figure 1, 35.

[2]. Samuel de Champlain, Carte Geographique de la Nouvelle France, (1612), Appendix, Figure 5.

[3]. Chad Anderson, “Rediscovering Native North America: Settlements, Maps, and Empires in the Eastern Woodlands,” (Early American Studies 14, no. 3, 2016), 483.

Cartography, New England, & Exclusion

Early 17th century cartography of New England was largely done by highly experienced Dutch cartographers based in New Amsterdam, which is current day New York. The few British cartographies after John Smith’s map of 1616 and predating 1675 are very simplistic and geographical distances are greatly distorted.

The British in New England were struggling to gain a stronger presence and began to speculate on land. The first generation of English settlers and Indigenous people heavily relied on and adhered to treaties and accords for a peaceful coexistence. The subsequent generation of English settlers wanting more territory than they were allotted. According to Greer, the English settlers began to take advantage of weak treaties, tribes decimated by diseases and warfare, and easily bribed tribal leaders to secure more land.[1] Among the many factors that led to war, including being forced off land, the creation of praying towns, British livestock decimating Indigenous crops and hunting grounds, and the murder of John Sassamon, the common factor was the realization by the Indigenous people that they were being erased from their own landscape.[2] Open warfare lasted from 1675 to 1676, and ended with the death of Metacomet (King Phillip) and the capture, surrender, and decimation of much of the Indigenous people of southern New England.[3] The English settlers suddenly, and violently, confiscated lands that once belonged to Indigenous people and their first course of action was to chart this new area justifying their legal claim to this territory

[1]. Greer, Property and Dispossession, 229.

[2]. Praying towns were small villages created to convert Indigenous people to Christianity and to integrate them into English society. While many Indigenous people did participate in Praying Towns, the English still marginalized the Praying Indians, keeping them on the outskirts of society. For more information about the causes of King Phillip’s War, including Praying Towns and the impact of English livestock on Indigenous lands, reference Philip Ranlet’s “Another Look at the Causes of King Phillip’s War,” and Virginia DeJohn Anderson’s “King Philip’s Herds: Indians, Colonists, and the Problem of Livestock in Early New England.”

[3]. Lisa Tanya Brooks, Our Beloved Kin: A New History of King Philip’s War, (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2018), 301.

The War of Maps

With the British crown stabilizing and expanding imperialistic control over their territories in North America came a boundary dispute with the French crown over how to interpret sovereignty in colonial territories. The French defined their territorial areas as any land near the Mississippi River which was charted by French explorer Robert de la Salle, and all unexplored tributary areas of the Mississippi. The British, contrastingly, defined their boundaries using the Treaty of Utrecht, which was signed in 1713.[1] The French ceded North American territories to Britain, which included Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, and the Hudson Bay territory. France recognized British control of this area. The British then justified pushing their territorial boundaries in North America as they were now allied with the Iroquois through the Treaty of Utrecht. The British considered that any territorial lands of the Iroquois were now their territory as well.[2] British and French boundaries began to overlap.

[1]. Susan Schulten, A History of America in 100 Maps, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), 66.

[2]. Schulten, A History of America in 100 Maps, 66.